NEW YORK FLOWERS: ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

The pieces of Mapplethorpe's puzzle that have spread over the last decades appear too intimately complex to put back together. From newspapers articles to academic reviews, facts mean facts, sometimes subjectively objective. Allowing a conversation between them and suppositions opens new doors for the mind to explore; new sides of the photographer. A controversiality perhaps not that much black or white.

The Controversial Exhibition

“1990 Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center director Dennis Barrie is charged with violating obscenity laws for presenting Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment.

He is acquitted by a jury“

(Atkins, 1991, p.37).

Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment was a retrospective exhibition organised by the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Philadelphia in 1988, presenting the work of photographer Robert Mapplethorpe from the late 1960s to 1988; curated as a traveling exhibition, it was supposed to be seen at five other museums over the next year and a half, after it closed at ICA. It is worth mentioning that the show of more than 150 images happened in Philadelphia without incident from December 1988 through January 1989, just shortly before Mapplethorpe died of AIDS in March 1989.

It then travelled to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, “again without generating any unusual public attention or raising legal questions about obscenity in relation to the content of the work“ (Tannenbaum, 1991, p.71). When the turn came to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D. C. to exhibit it in June 1989, “ICA was unexpectedly thrust into the national spotlight,“ as explained by Judith Tannenbaum (1991, p.71), assistant director of ICA at the time. That exhibition brought an intense debate about federal funding of the arts, as well as “ultimately, the focus of an obscenity trial in Cincinnati“ (Idem). Senator Jesse Helms accused Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment to be a controversial photographic exhibition, promoting pornography and obscenity, as described by Deborah A. Levinson in an article for The Tech newspaper in August 1990 (Rinehart, 2010, p.187).

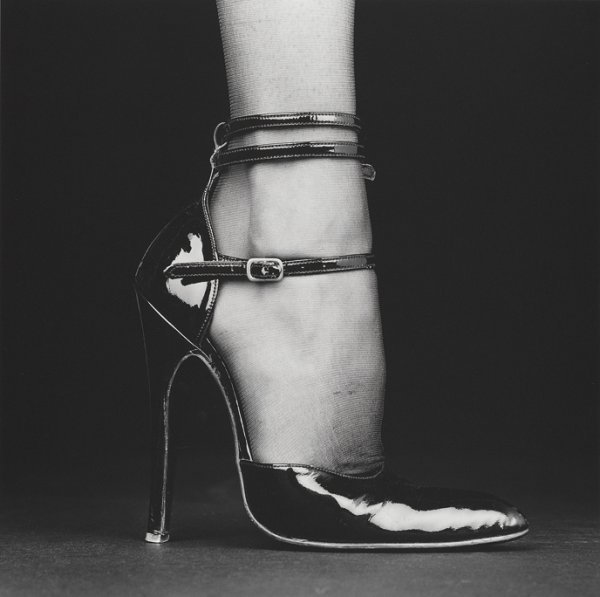

If interested in the concept of dichotomy first and foremost, keep on reading, as it draws the background of the entirety of Mapplethorpe's portfolio: from his powerful and soul-baring portraits, his perfectly yet raw floral imagery as well as his most disturbing and dark visuals, translating the gay community of the ‘70s on the New York underground scene. His photographic work fully embodies the idea of dichotomy and contradiction, as it was all about opposing black and white, heaven and hell, good and evil, high art and low subculture, beauty and ugliness, normative and subversive, exposure and secrecy, intimate and formal, life and death, emptiness and fullness, sexuality and porn, classical and modern, violence and sensibility to name but a few.

The Dark Room

“I was able to pick up the magic of the moment. […] You get to a place. You don’t know why it’s happening but it’s happening. You can do it with flowers, with cocks […],“

these were the words of Robert Mapplethorpe in the documentary titled with his name, created by the BBC in 1988. The general public reminds him as the provocative photographer, breathing only to disturb, as newspapers’ titles at the time questioned: “Is Mapplethorpe only out to shock?“

However, as the documentary illustrates through the words of the artist himself and his close friends, Mapplethorpe used to believe in magic and started chasing after it in the late '60s, start of the '70s. It is undeniable that he “titillates the art world with his photography because of aesthetics 'highly ambiguous,' as novelist Edmund White describes (cited in Robert Mapplethorpe, 1988). Against all expectations, Mapplethorpe used to tell his process as

“being sensitive about the person. I don’t want to make them go through something unnecessary. […] You have to like them [the people you photograph] for the time of the picture.“

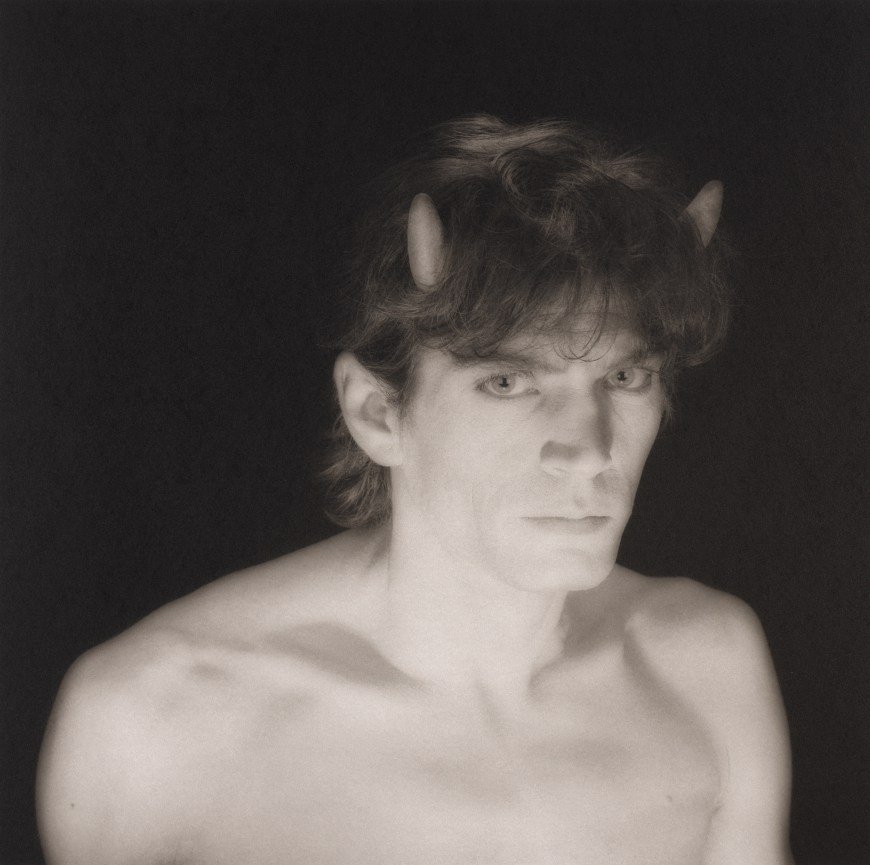

©Robert Mapplethorpe, Self-Portrait (1985)

Even though his work appears to make a social statement, he used to question it through a self-portrait wearing horns: “There’s a sense of humour in what I am doing. I hope that people pick up on it. […] More serious than that you know, how would I look like if I had horns. Is that making a statement about myself? It’s one aspect of everybody.

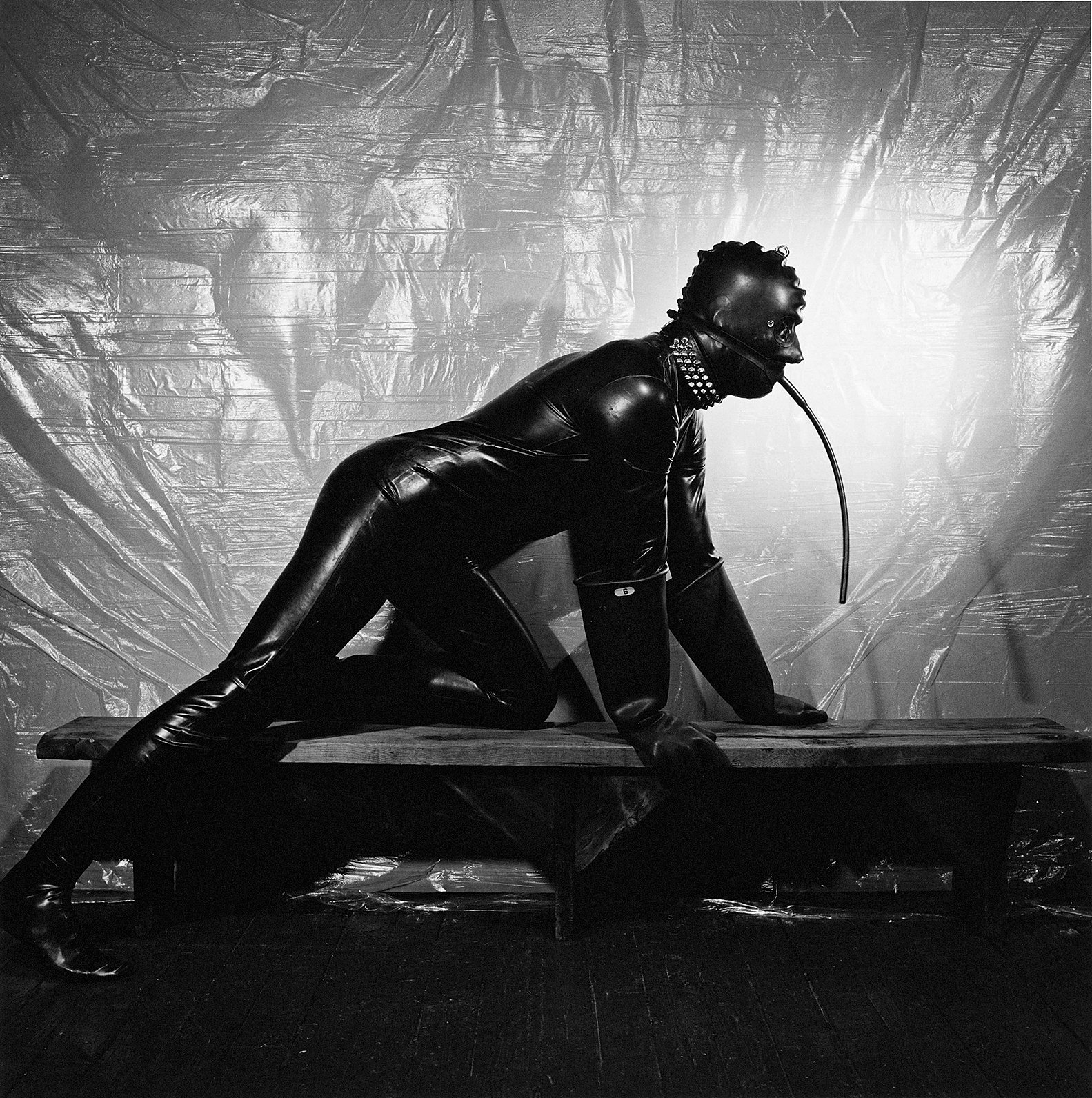

Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio

“There was a feeling I could get by looking at pornographic images. That was never been apparent in art. It somehow retained that feeling. Maybe it was the forbidden […] That, if I could get across and make an art statement, do it in a way that would reach a certain kind of perfection. Then I would be doing something that was uniquely my art.“ – Robert Mapplethorpe, 1988.

These words recall the time when Mapplethorpe joined the underground gay community at The Mine Shaft in New York, in other words “this period of Mapplethorpe’s output which arouses most hostility: calculated images of aggressive sexuality, coldly absorbed in emptied moral content“ (Robin Gibson cited in Robert Mapplethorpe, 1988). A lifestyle that most certainly generated the red thread of the X Portfolio, composed of homoerotic sadomasochistic images.

Of a raw yet hypnotising beauty, the X Portfolio forces the viewers to flirt with vulnerability, unsettling their individual relation to sensuality in all its forms. Photographer and friend of the artist, Lynn Davis, depicted him and his work in saying that “Robert sets the tone. It’s cool and it’s a bit under the surface. […] There’s a kind of detachment and honesty in it. […] He can look at all in the face. Whatever it is. If it’s a flower, if it’s beauty […]“ (cited in Robert Mapplethorpe, 1988).

The artist's portfolios are displayed with a series of poems by poet and singer Patti Smith. The prose poems, which are structured as free associations on the letters X, Y, and Z, go straight to the heart of Mapplethorpe’s work: ‘Y is the symbol of the covenant which exists between the artist and his creator/ Y is the consummation of this idea thru the projection of the perfection shot' (cited in Deborah Levinson, 1990, p.14).

In-between the surface and depth, Mapplethorpe craved physicality; the X Portfolio illustrates the transcendental power of his aesthetics. On the other hand, when Patti Smith shares the main theme, which inspired herself and his friend and ex-lover, as “the struggle between heaven and Earth, good and evil“ (cited in Robert Mapplethorpe, 1988), it redirects the interpretation towards a more conceptual, if not religious and philosophical universe.

“It wasn’t about what the subject is but what the subject seems. […] It’s sort of amazes me. They’re [flowers] not sweet. And you know they’re New York flowers,“

she used to explain (Patti Smith cited in Robert Mapplethorpe, 1988). When Patti Smith brings a more human aspect to the understanding of The Perfect Moment exhibition and the very loud psychological impact that it provoked, there still remains the big picture. Mapplethorpe indeed has not only shaken how to mirror society but also and most importantly the art world itself and how the laws used to apply to it in terms of intrinsic freedom: who has the right to value what can be called art or not, and on a larger scale, why has society the right to decide what has to be seen or not. +